Remote-Work Options Can Boost Productivity and Curb Burnout (Report)

Boost Productivity with Remote-Work Options

The pandemic accelerated the availability of remote-work access sooner than many prognosticators and employers anticipated.1 But we should regard remote work as more than a solution to a one-time crisis. In fact, remote work is the way of the future, as many employees now say they prefer working remotely at least some of the time.2 Organizations have good reason to embrace remote work; Catalyst research finds that access to remote work makes a difference for employee well-being, productivity, innovation, and inclusion.

As part of our Equity in the Future of Work research series, Catalyst surveyed 7,487 employees across the globe.3 Our data show that when employees who have access to remote-work options—including flexible work location, distributed teams, and/or virtual work/telework/working from home—are compared with employees lacking these options, their access is linked to: 4

A Silent Crisis at Work: Burnout

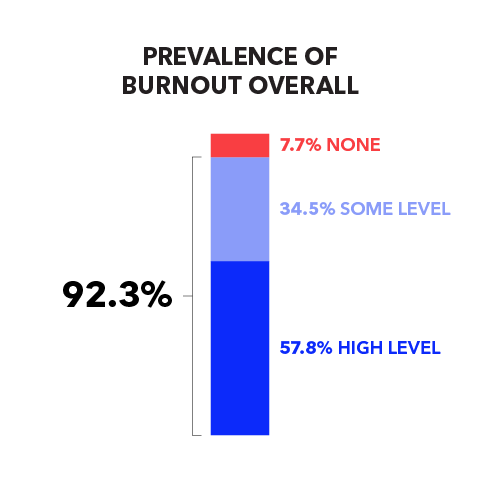

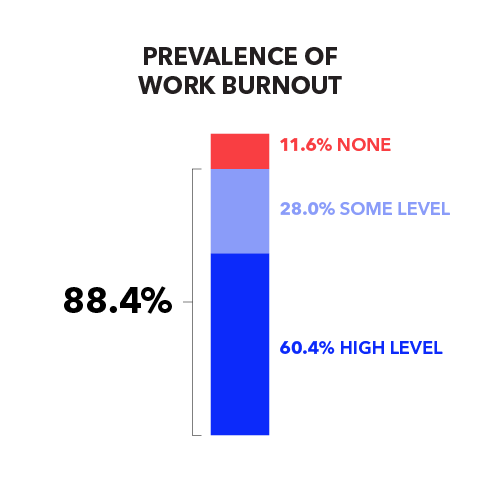

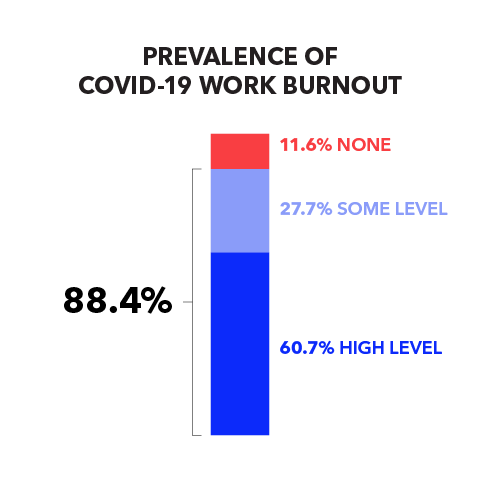

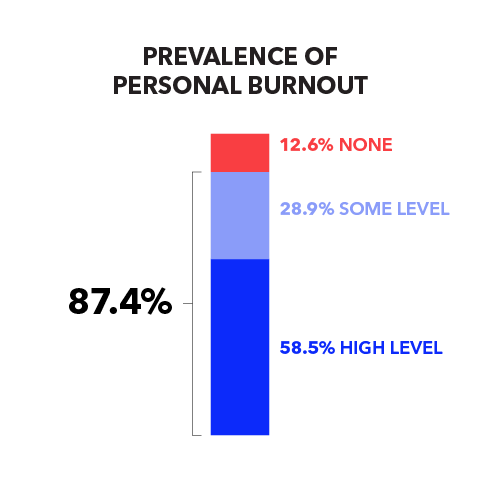

At the same time, the pandemic has exacerbated a silent crisis at work: the rise of burnout, the physical and psychological exhaustion that comes from prolonged stress with negative consequences, including mental distance from one’s job and feelings of professional inefficacy.11 Our global survey found that the vast majority of those surveyed—92.3%—are experiencing some amount of burnout.12 Their burnout is a result of stress related to their workplace in general, Covid-19 work experiences in particular, and/or factors in their personal lives.

Remote-Work Options Can Alleviate Employee Burnout

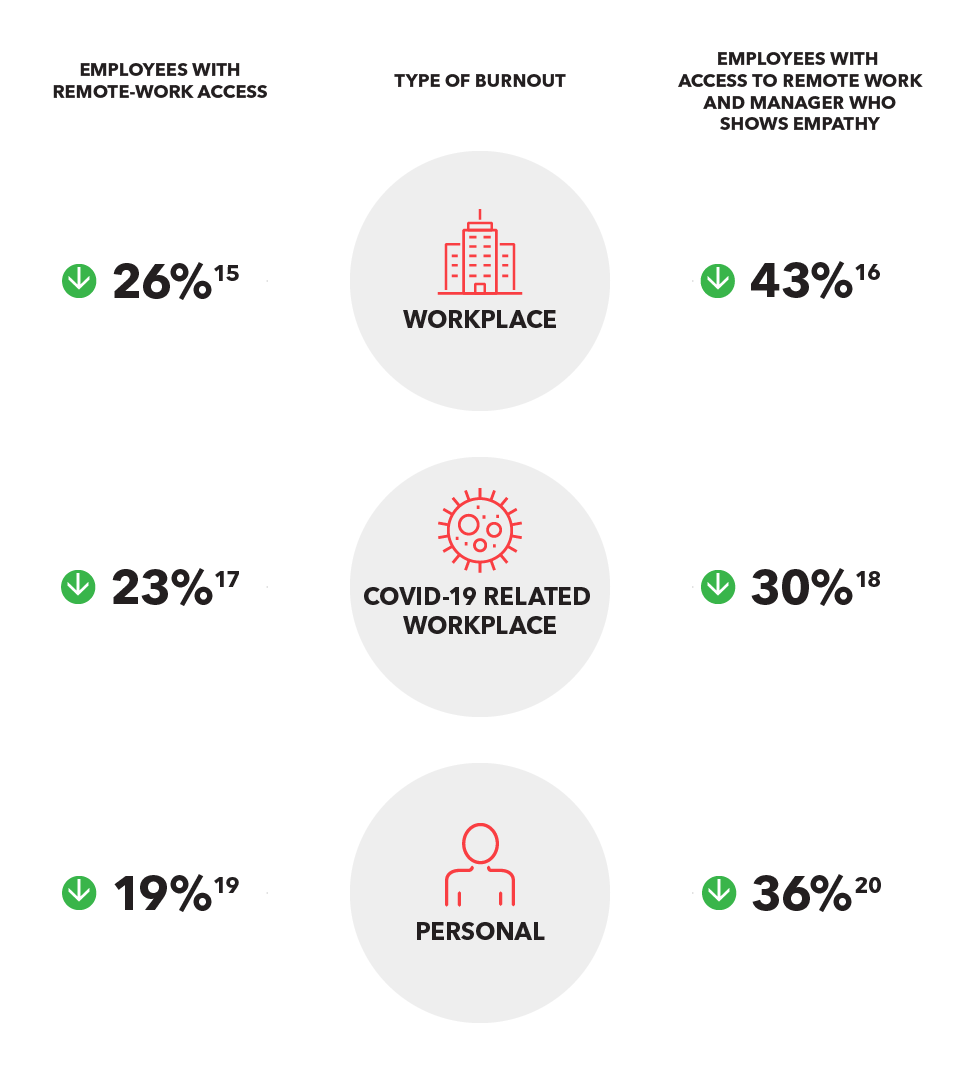

Widespread workplace burnout at the employee level can be a symptom of larger organizational challenges.13 Our research shows that organizations should address some of these challenges by offering remote-work options to employees—alleviating burnout and also significantly benefiting employees and organizations in other ways.

Our data show that when companies offer options to work remotely, employees reported decreased experiences of all three types of burnout, compared to employees without remote-work access. And when managers additionally demonstrate empathy,14 burnout is further decreased.

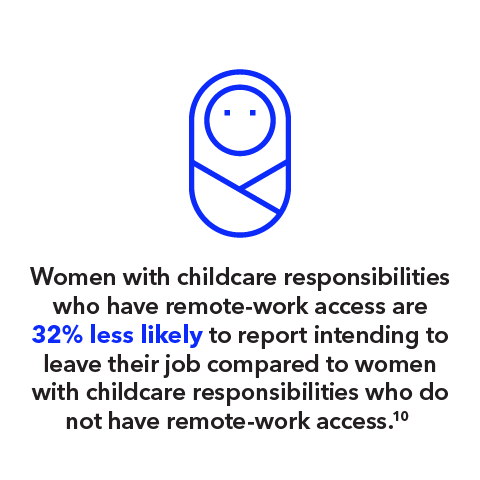

These findings are especially important for women, who have been affected disproportionately by the pressures of working during a pandemic. Across the globe, it is estimated that women lost over 64 million jobs in 2020, costing them at least $800 billion in income.21 In the US alone, over two million women have left the workforce, many to take on additional childcare responsibilities.22 In addition, 24% of US executive women plan to leave due to their companies’ response to the pandemic.23 Remote-work options and manager empathy for individual situations can provide critical support for women, especially mothers, through this pandemic and beyond by signaling care, support, and inclusion for all employees and their life circumstances.

What Leaders Can Do

These findings add to a growing body of research on the positive benefits remote-work access can have for life-work integration and productivity. However, remote work also has been shown to lead to longer hours without adequate pay and recognition.24

To avoid the pitfalls of remote work while reaping its benefits, organizations and leaders must create a culture of remote work that is sustainable, equitable, and humane. Guardrails that restrain unsustainable workloads and “always-on” expectations and tendencies, training to develop empathy and inclusion, and flexible work policies are key.

To invest in the tools and training that will ensure all employees can thrive—whether they’re working remotely full-time, part-time, or occasionally—start with the following steps:

- Create remote-work policies that detail expectations for employees, managers, and teams.25

- Upskill managers on managing remote teams inclusively.26

- Invest in programs and stipends for employees who need additional childcare options.27

- Normalize empathic listening through regular check-ins and other opportunities to share life and work experiences.28

Organizations across the globe are responding to this watershed moment in the world of work—an unprecedented opportunity to rebuild workplaces that are inclusive for all employees and support them in their specific life circumstances. By implementing remote work with flexibility and inclusion at the core, organizations are setting themselves apart from their peers, attracting top talent unbound by location parameters, and innovating at a faster pace.

Acknowledgments

Dell

DSM Brighter Living Foundation

KPMG

Sodexo

CIBC

Guardian Life Insurance Company of America

Lema Charitable Fund

Pitney Bowes Inc.

How to cite: Van Bommel, T. (2021). Remote-work options can boost productivity and curb burnout. Catalyst.

Endnotes

- Pasquarella Daley, L. (2019). Women and the future of work. Catalyst.

- 2021 Work Trend Index: The next great disruption is hybrid work—Are we ready? (2021). Microsoft; The 2021 state of remote work. (2021). Buffer; DelBene, K. (2021, March 22). The philosophy and practice of our hybrid workplace. Microsoft.

- We conducted an online survey about work experiences during the coronavirus pandemic from September to November 2020 targeting employees working full-time across a variety of industries. The majority come from one of the following 14 countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Mexico, Netherlands, Singapore, Sweden, UK, and the US.

- Note that for all models reported we also analyzed group differences by gender and by child caregiving status and only significant findings are reported herein. That is, gender and child caregiving did not significantly moderate the affect of remote-work access for any of the outcomes apart from intent to leave (see endnote 10 for findings).

- Employee innovation is measured with five self-report items from the Catalyst Inclusion Accelerator assessed on a 1 (never) to 5 (always) Likert scale; these items were used to create a composite (α = .87) where higher values indicate a greater degree of innovative behaviors at work; this composite was dichotomized for analysis in a binary logistic regression. A binary logistic regression analysis examined the impact of access to remote work (0 = no and 1 = yes) on self-reported innovation at work (0 = never/rarely/sometimes and 1 = often/always). Nagelkerke R2 = .02, Χ2 (1) = 74.56, p < .001. For people with remote-work access, the probability of often or always being innovative increases by 63% (Wald (df=1, N=6630) = 72.88, OR = 1.63, p <. 001) compared to people without remote-work access.

- Employee work engagement is measured with five self-report items from the Catalyst Inclusion Accelerator assessed on a 1 (never) to 5 (always) Likert scale. These items were used to create a composite (α = .90) where higher ratings indicate greater work engagement. A binary logistic regression analysis examined the impact of access to remote work (0 = no and 1 = yes) on self-reported engagement at work (0 = never/rarely/sometimes and 1 = often/always). Nagelkerke R2 = .03, Χ2 (1) = 124.75, p < .001. For people with remote-work access, the probability of often or always being engaged increases by 75% (Wald (df=1, N=6620) = 123.12, OR = 1.75, p <. 001) compared to people without remote-work access.

- Organizational commitment is composite of two items (r = .53, p <.001; loyalty to one’s organization and feeling one can advance at their organization) assessed on a 1 (very untrue) to 5 (very true) Likert scale; this composite was dichotomized for analysis in a binary logistic regression. A binary logistic regression analysis examined the impact of access to remote work (0 = no and 1 = yes) on self-reported organizational commitment (0 = very untrue/untrue/neutral and 1 = true/very true). Nagelkerke R2 = .02, Χ2 (1) = 108.28, p < .001. For people with remote-work access, the probability of often or always being innovative increases by 68% (Wald (df=1, N=6607) = 107.55, OR = 1.68, p <. 001) compared to people without remote-work access.

- Employee inclusion is measured with five items from the Catalyst Inclusion Accelerator assessed on a 1 (never) to 5 (always) Likert scale; these items were used to create a composite (α = .74) where higher values indicate a greater degree of inclusion at work; this composite was dichotomized for analysis in a binary logistic regression. A binary logistic regression analysis examined the impact of access to remote work (0 = no and 1 = yes) on self-reported inclusion at work (0 = never/rarely/sometimes and 1 = often/always) Nagelkerke R2 = .03, Χ2 (1) = 146.64, p < .001. For people with remote-work access, the probability of often or always experiencing inclusion increases by 93% (Wald (df=1, N=6900) = 141.70, OR = 1.93, p <. 001) compared to people without remote-work access.

- Intent to leave is a single item (How likely are you to look for another job in the next year?) measured on a 1 (not at all likely) to 5 (very likely) Likert scale; this composite was dichotomized for analysis in a binary logistic regression. A binary logistic regression analysis examined the impact of access to remote work (0 = no and 1 = yes) on self-reported intent to leave (0 = not at all likely/a little likely and 1 = somewhat/most/very likely) Nagelkerke R2 = .01, Χ2 (1) = 50.91, p < .001. For people with remote-work access, the probability of being likely to look for another job in the next year decreases by 30% (Wald (df=1, N=6602) = 50.79, OR = .70, p <. 001) compared to people without remote-work access.

- Including self-identified women only in the analysis, a binary logistic regression analysis examined the impact of access to remote work (0 = no and 1 = yes), child caregiving status (“do you have any child caregiving responsibilities?”) (0 = no and 1 = yes), and their interaction on self-reported intent to leave (0 = not at all/a little likely and 1 = somewhat/most/very likely). Nagelkerke R2 = .01, Χ2 (3) = 33.01, p < .001. For women with child caregiving responsibilities who have remote-work access, the probability of being likely to look for another job in the next year decreases by 32% (Wald (df=1, N=3112) = 6.45, OR = .68, p <. 01) compared to women with child caregiving responsibilities without remote-work access.

- International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 11th revision. (2019). World Health Organization; Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. (2019, May 28). World Health Organization.

- Burnout was assessed on a ten-point scale (1 = not at all burned out, 10 = extremely burned out) using the single-item burnout measure: Hansen, V. & Pit, S. (2016). The single item burnout measure is a psychometrically sound tool for screening occupational burnout. Health Scope, 5(2), e32164. In validation of the Single-Item Burnout scale (Hansen & Pit, 2016), a cut-off of five or higher was determined to align with previous measures of burnout and to accurately characterize “high burnout”; thus, high burnout was characterized as five or higher in the current data.

- Garton, E. (2017, April 6). Employee burnout is a problem with the company, not the person. Harvard Business Review; Khazan, O. (2021, March 12). Only your boss can cure your burnout. The Atlantic.

- Manager empathy was measured with a scale adapted from the medical literature that assesses patients’ experiences of empathy in interactions with their doctor: The consultation and relational empathy measure (CARE); Mercer, S.W., Maxwell, M., Heaney, C., & Watt, G. C. (2004). The consultation and relational empathy (CARE) measure: Development and preliminary validation and reliability of an empathy-based consultation process measure. Family Practice, (21)6, 699-705. This scale was chosen because it reflects empathy experienced in interactions (i.e., second-person empathy); many other available scales tap an individual’s level of empathy as they engage with others, (i.e., first-person empathy). The ten-item scale was adapted for interactions with direct managers and an additional seven items derived from Catalyst’s conceptualization of empathy (Pasquarella Daley, L., Van Bommel, T., & Brassel, S. (2020). Why empathy is a superpower in the future of work. Catalyst.) were added for a total of 17 items; the scale showed excellent internal reliability, α = .97.

- A binary logistic regression analysis examined the impact of access to remote work (0 = no and 1 = yes) on self-reported general workplace burnout (0 = low burnout and 1 = high burnout). Nagelkerke R2 = .01, Χ2 (1) = 35.56, p < .001. For people with remote-work access, the probability of experiencing high levels of general workplace burnout decreases by 26% (Wald (df=1, N=6594) = 35.33, OR = .74, p <. 001) compared to people without remote-work access.

- A binary logistic regression analysis examined the impact of access to remote work (0 = no and 1 = yes), manager empathy (0 = poor/fair and 1 = good/very good/excellent), and their interaction on self-reported general workplace burnout (0 = low burnout 1 = high burnout). Nagelkerke R2 = 0.02, Χ2 (3) = 85.37, p < .001. For people with remote-work access and manager empathy, the probability of experiencing high levels of general workplace burnout decreases by 43% (Wald (df=1, N=6594) = 27.66, OR = .57, p <. 001) compared to people without remote-work access and without empathic managers.

- A binary logistic regression analysis examined the impact of access to remote work (0 = no and 1 = yes) on self-reported burnout due to Covid-19 related factors in one’s workplace (0 = low burnout 1 = high burnout). Nagelkerke R2 = .01, Χ2 (1) = 25.61, p < .001. For people with remote-work access, the probability of experiencing high levels of Covid-19 related work burnout decreases by 23% (Wald (df=1, N=6594) = 25.48, OR = .77, p <. 001) compared to people without remote-work access.

- A binary logistic regression analysis examined the impact of access to remote work (0 = no and 1 = yes), manager empathy (0=poor/fair and 1 = good/very good/excellent), and their interaction on self-reported burnout due to Covid-19 related factors in one’s workplace (0 = low burnout 1 = high burnout). Nagelkerke R2 = .01, Χ2 (1) = 38.30, p < .001. For people with remote-work access and manager empathy, the probability of experiencing high levels of Covid-19 related workplace burnout decreases by 30% (Wald (df=1, N=6594) = 11.31, OR = .70, p <. 001) compared to people without remote-work access and without empathic managers.

- A binary logistic regression analysis examined the impact of access to remote work (0 = no and 1 = yes) on self-reported burnout due to factors in one’s personal life (0 = low burnout 1 = high burnout). Nagelkerke R2 = .003, Χ2 (1) = 17.05, p < .001. For people with remote-work access, the probability of experiencing high levels of personal burnout decreases by 19% (Wald (df=1, N=6594) = 17.00, OR = .81, p <. 001) compared to people without remote-work access.

- A binary logistic regression analysis examined the impact of access to remote work (0 = no and 1 = yes), manager empathy (0=poor/fair and 1 = good/very good/excellent), and their interaction on self-reported burnout due to factors in one’s personal life (0 = low burnout 1 = high burnout). Nagelkerke R2 = .01, Χ2 (3) = 34.64, p < .001. For people with remote-work access and manager empathy, the probability of experiencing high levels of personal burnout decreases by 36% (Wald (df=1, N=6594) = 17.56, OR = .64, p <. 001) compared to people without remote-work access and without empathic managers,

- Covid-19 cost women globally over $800 billion in lost income in one year. (2021, April 29). Oxfam International.

- Matuson, R. (2021, March 1). How to stop the mass exodus of women leaving the workforce due to Covid-19. Forbes; Sasser Modestino, A., Ladge, J. J., Swartz, A., & Lincoln, A. (2021, April 29). Childcare is a business issue. Harvard Business Review.

- Stych, A. (2020, December 7). Executive women shoulder the burden as pandemic stresses caregivers, Chief survey finds. Bizwomen.

- Tayeb, Z. (2021, April 25). Working from home means longer hours, fewer sick days, and fewer bonuses, according to a major report. We break down 4 of its key findings. Insider.

- Ask Catalyst Express: Inclusive Hybrid Workplaces. (2021). Catalyst

- Managing remote teams inclusively: Knowledge burst. (2020). Catalyst.

- Cutter, C. & Glazer, E. (2021, February 28). Pay cuts, taxes, child care: What another year of remote work will look like. The Wall Street Journal.

- Flip the script: Empathy in the workplace. (2021). Catalyst.